I read to my daughter a lot. She's only three but we ensure that we read at least three books before she goes to bed. The other night I had a direct experience that brought home to me the difference between biologically primary and secondary knowledge, the important distinction made by Geary. To those who aren't familiar with this distinction, it says that there are certain aspects of cognition such as communication, collaboration and general means to end problem-solving ability that occur "naturally" and cannot be directly taught. By contrast, secondary “schematic” knowledge takes time and effort to build up and requires explicit instruction. I believe most English teachers will recognise how revolutionary these ideas are to the teaching of our subject because we spend a lot of time trying to get kids to improve their ability to "infer" or "read between the lines" as if these can be abstractly separated and trained independently of the context in which they are being employed. The evidence suggests they can't be.

Teaching "analysis" often involves trying to improve students ability to "read between the lines" or infer things that are not at once obvious in a text. The process is key to identifying the underlying authorial purpose. For a long while, I thought that this was a skill that happened independently of what kids knew. I would give students individual lines from poems and ask them to "infer" as much as they could from those single lines. I would also do a class where I would present the shopping receipts of unknown strangers and get them to infer, in groups, as much as they could about those people. Another favourite would be to look at a painting and attempt to infer as much as possible about the artist's life or intentions, hoping to transfer that skill across to texts. I treated inferring like a skill that could be strengthened through repetition. Now, back to my daughter and our bedtime reading habits.

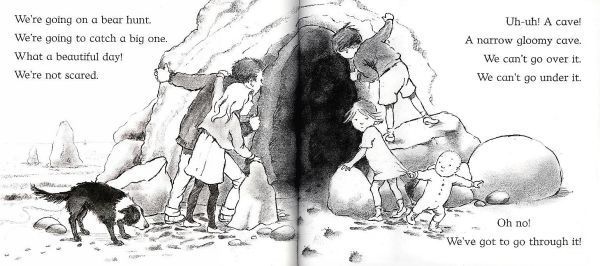

One of our favourite books is "We're going on a Bear Hunt". For those who don't know it, this is a wonderful, classic English fairytale. An intrepid family sets off "to hunt a bear" passing various natural obstacles along the way from precipitation to a river and a dark forest. The height of tension is when the family reach a cave where a bear really is hiding... When they arrive at the cave, there is the following picture.

Take a look at the baby in the bottom right, what's he doing? He looks like he's trying to pull his sister away from the cave. Clearly, he has some kind of insight into the perils of their situation; this baby is onto something. When we "work this out" it feels like we are using our "higher-order" thinking skills to understand it. Conceivably, we could "infer" that there was something going on whilst being pretty unfamiliar with the text, or reading it for the first time. Still, we look at that picture and there is something going on that is not explicitly stated. There is something that needs to be "read into" the image of the baby. The conclusion, "he knows that there is something inside the cave" isn't an obvious one to reach even for a five or six-year-old.

We look at that baby and use our powers of inference to read what is not directly said and understand that he knows there is a bear inside and wants to take them away from the danger. My approach to teaching before understanding a bit about cognitive load theory was that this "power" could be developed independently of context. Essentially by doing this piece of inference in this text, I'd be better at doing other inferences in other contexts. I would become a more skilful reader.

We look at that baby and use our powers of inference to read what is not directly said and understand that he knows there is a bear inside and wants to take them away from the danger. My approach to teaching before understanding a bit about cognitive load theory was that this "power" could be developed independently of context. Essentially by doing this piece of inference in this text, I'd be better at doing other inferences in other contexts. I would become a more skilful reader.

Whilst reading this with my daughter I was presented with some evidence of the proposition that general cognitive abilities develop quite naturally and without instruction in young children. My daughter looked at it, remember she's three, and she said: "look Daddy he knows there is a bear inside and he's pulling her away". She just did it. No one told her to read between the lines. The point I am trying to make is we all infer all the time, life is about making inferences in a range of different situations. There is nothing "special" about the act of inferring itself. What makes any inference either "successful" or "unsuccessful" is knowledge of the domain we are inferring from. Because she has that deep understanding of the domain she is more able to "read between the lines". Importantly, the fact she was able to do that in this case in no way suggests that she is, therefore, able to infer in a different text that she is not familiar with. This really hammered home for me the point that inferring is not a generic skill you can train but something that occurs when someone has deeply embedded subject knowledge in a domain. When she knew the text well enough, almost by heart, there came the ability to notice the small details that give the text life and depth.

When we really dominate a domain and have deep mastery of the schema involved, that knowledge becomes more flexible and enables us to have greater insight. The part of actually doing the inference is fairly arbitrary, what's not arbitrary is the hard work of actually coming to understand the text in the first place.

For those that don't work in schools, quite a lot of time is spent working on reading comprehension "skills" such as reading between the lines and inferring as if these aspects of cognition are independent of the subject matter. We have it the wrong way around. Certain aspects of cognition, like inferring things from people's facial expressions and body language, occur without effort. We literally cannot survive without inferring things from limited information. However, we cannot "get better" at doing that through practice. Essentially what makes the inferences more accurate or insightful is the quality and extent of the information in long term memory that frees up working memory capacity to focus on other things. Inferring "in itself" cannot be taught or improved. That's why getting kids to practice "finding the main idea" in a text is often a waste of time. Whether or not a kid can truly comprehend a text will depend on their level of familiarity with the contents of whatever they are reading; it doesn't matter how many times you practice inferring you cannot get better at it in the abstract sense.

What we should therefore teach is the deep knowledge and skill that fuel inference. The process of the inference itself isn't that important, we all do it. What's important is depth and breadth of knowledge from which those inferences occur naturally. We need to start from the material, from the content, and build up those knowledge structures in long term memory. The "thinking about it" part takes care of itself. The example of my daughter doing quite naturally what is sometimes thought about as "higher level cognitive skills" shows me that.

For those that don't work in schools, quite a lot of time is spent working on reading comprehension "skills" such as reading between the lines and inferring as if these aspects of cognition are independent of the subject matter. We have it the wrong way around. Certain aspects of cognition, like inferring things from people's facial expressions and body language, occur without effort. We literally cannot survive without inferring things from limited information. However, we cannot "get better" at doing that through practice. Essentially what makes the inferences more accurate or insightful is the quality and extent of the information in long term memory that frees up working memory capacity to focus on other things. Inferring "in itself" cannot be taught or improved. That's why getting kids to practice "finding the main idea" in a text is often a waste of time. Whether or not a kid can truly comprehend a text will depend on their level of familiarity with the contents of whatever they are reading; it doesn't matter how many times you practice inferring you cannot get better at it in the abstract sense.

What we should therefore teach is the deep knowledge and skill that fuel inference. The process of the inference itself isn't that important, we all do it. What's important is depth and breadth of knowledge from which those inferences occur naturally. We need to start from the material, from the content, and build up those knowledge structures in long term memory. The "thinking about it" part takes care of itself. The example of my daughter doing quite naturally what is sometimes thought about as "higher level cognitive skills" shows me that.

I think I could have guided her towards doing this through questioning, I could have asked "why is he pulling her away" and if she thought about it enough she might have been able to "work it out". Perhaps you would argue that by doing this, they would develop the "habit" of inferring or perhaps even become more "aware" of their thinking and so develop metacognition. I disagree. I do think it's useful to know the definition of the concept "to infer" but the fact that a three-year-old does it so naturally and without any instruction as a result of knowledge suggests strongly to me that those processes will "just happen" and that our best bet for, as David Didau would say, "making kids more intelligent" is increasing the strength and depth of their knowledge knowing that the biologically primary elements of cognition will flourish given a normal healthy upbringing.

So what we need yo do is read to and with our children. Let them enjoy stories so much that they end up learning them by hard. If we work with them with languages skills will be helping them to develope infinite other skils. Same thing happends with math skills, we can teach them by playing, our Chilean teaching sistem needs to change!

ReplyDeleteAre you saying we "can't" teach them by playing?

DeleteLove this, James.

ReplyDeleteWhen I encounter teachers who tell me their students need to learn how to make inferences, I tell them this very short story, modified from Benjamin Bergen's excellent book, "Louder Than Words: The New Science of How the Mind Makes Meaning":

Polar bears love seal meat. Seals, however, are very quick and very hard to catch. So polar bears have evolved to use a very clever way to sneak up on seals. The bears lower their chest onto the ground and use their rear legs to slide themselves forward, all the time using one front paw to cover their nose!

Then I ask, why does the bear cover its nose with its paw? Invariably, someone replies, "Because the bear's nose is black, so their white paw makes sure the bear blends in with the snow and ice."

"That's right!" I say. Then I say, "Notice I never mentioned any color, nor that polar bears live in an environment that is covered in ice and snow. You added that information to answer the question."

Everyone I've told this to looks somewhat surprised at first, then realizes that I'm right, I never mentioned a color or the setting. The listener created what's called a situation model, a mental image of the scene.

That's all inferencing is, I say, it's filling in the information that the speaker or writer assumed you already know.

Instead, too many teachers think of inferencing as something like the procedure for solving a mathematical equation, and once students learn that procedure, they'll be able to "solve" any inference they encounter in their reading.

All the cognitive science and cognitive psychology I've read supports what you're claiming in this blog, James: we are wired to make to make meaning, therefore, we are wired to make inferences. The question is, do we have the knowledge stored in long-term memory to make the correct inference?

It's also possible, of course, to have so little knowledge about a topic that we're forced to do what my students used to do at times: read a text, raise a hand, and say, "That makes absolutely no sense."

I wish I'd understood about inferencing much, much sooner. For too long my reply to the "That makes no sense" comment was to ask, "What about it doesn't make sense?" All the students in that situation could do is point at the text again and say something like, "The whole thing!"

Now I know that I should have been anticipating, as best I could, gaps in my students' background knowledge and pre-teaching that. And if I still got the "That makes no sense" comment, I'd start by asking specific questions, like, "Do you know where polar bears live?" and "Do you know what color polar bears are?"

Oh, one more thing: the story of polar bears hunting like that is completely apocryphal. :-)