Are we obsessed with "normalizing" children? Talk too much? Talk less. Don't talk enough? Talk more. Disorganized? Buy a ring binder. Hyper-organized? Let it go. Perfectionist? Make more mistakes. Careless? Make fewer mistakes! It's all part of being a teacher, we want to help kids be their best selves. When it becomes a problem is when healthy childish behaviors are deemed to be representative of some underlying, yet-to-be-diagnosed disorder.

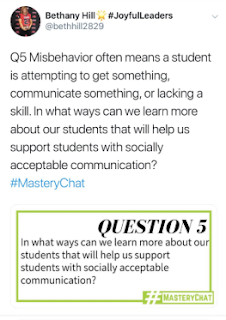

As a profession, we are at a stage where the dominant discourse around what can and should be done to improve behaviour in schools is encouraging such a pathologization of childhood. The ultimate expression of this is the idea that "all behaviour is the communication of an unmet need". The discussion around how to manage behaviour is that negative consequences for undesirable behaviour are "outdated" and instead we should seek out some underlying cause. In some cases, any form of negative consequence or correction is violence or aggression, entirely independently of the positive outcomes it might entail. We have reached a point of hyper-pathologization.

I have a four-year-old. Sometimes four-year-olds throw tantrums, lie, kick out and even spit (Lucy likes to make little spit pools and play with them). There is nothing wrong with her. She's a beautiful, well-adjusted four-year-old kid. When she messes about, I will firmly, with kindness and compassion, let her know her behaviour is not acceptable. If it continues, I will not positively reinforce that behaviour by giving her what she wants. Most importantly, my wife and I (not always very well!) try to be as consistent as possible. We are in the process of teaching her to sound out letters and words and she finds it challenging, of course. It's normal for her to resist this, it's easier for me to read it to her and I do that most of the time. However, when she becomes distracted I'll guide her back and encourage her to maintain focus. It doesn't mean I lock her in the chokey or take away her breakfast if she refuses to read; it does mean I consistently, compassionately and firmly draw her attention back to the work.

Why then do we take such a different approach with teenage boys? Throwing aeroplanes in class, avoiding homework, or throwing a cheeky comment to a teacher, is entirely normal. It is also entirely normal for a teacher to insist that this behaviour stops because it is distracting others from their learning. Indeed, if it wasn't normal for a teacher to want to stop this, the kid wouldn't do it. The whole point is that this isn't "allowed." Where's the fun in testing non-existent boundaries? In many schools, the rules and procedures are ambiguous or unclear so a huge amount depends on teacher discretion. If teachers ask for help with behaviour that is causing them trouble, they are told to give a choice, or make classes more engaging or build relationships. In other words, it's a pedagogical issue. All children are inherently well-behaved, but you are causing them not to be well-behaved by not meeting their needs.

Importantly, it IS the case that, of course, some behaviour is indicative of something more serious going on. My contention is that the overall approach of seeing most behaviour as communication as the "default strategy", combined with an absence of consistently enforced rules and a focus on pedagogical strategies such as giving choice and "building relationships", perpetuates a situation where normal challenging behaviour (often young males) is allowed to continue and comes to be seen as a pathology. Because this is the "default approach", behaviours which could be dealt with through improved consistency aren't dealt with and other behaviours amongst other pupils which don't cause disruption are ignored.

Importantly, it IS the case that, of course, some behaviour is indicative of something more serious going on. My contention is that the overall approach of seeing most behaviour as communication as the "default strategy", combined with an absence of consistently enforced rules and a focus on pedagogical strategies such as giving choice and "building relationships", perpetuates a situation where normal challenging behaviour (often young males) is allowed to continue and comes to be seen as a pathology. Because this is the "default approach", behaviours which could be dealt with through improved consistency aren't dealt with and other behaviours amongst other pupils which don't cause disruption are ignored.

To use an analogy with my daughter, if I gave her cartoons every-time, she wanted them she would be forever watching cartoons. Cartoons are entertaining, doing a puzzle or playing with some plasticine requires more effort. She will take the path of least resistance; it's my job as an adult to encourage her to take on more challenging things. When there is no agreed-upon, consistently implemented "system" for dealing with disruptive behaviour, each teacher is on their own and so going the less challenging route becomes more tempting! The kid who messes about because, yes, Math is annoying sometimes, is given less challenging work or allowed more freedom because it's easier than holding him accountable. Of course, that will improve the relationship because the child no longer has to do the thing he didn't want to do. The undesirable behaviour has been positively reinforced and is, therefore, likely to be repeated in other contexts. This process is how the pathologization of youth - mainly male children - occurs.

The "all behaviour is the communication of an unmet need" narrative can lead teachers to try and captain their ship using charisma and lowered expectations because they believe they need to prevent the kid from feeling stressed by the challenge of the work, and build relationships instead. Highly-successful ex-teachers who survived using charm, now working as consultants, encourage this. In some cases, the teacher might give up on the idea of a focused, calm, and orderly learning environment altogether because they just can't be that entertaining every day. Rambunctious boys suffer because they are confused about what is expected of them by different teachers. It's not a pathology to want to mess about and avoid work; it's normal childhood behaviour. Being more charismatic isn't a sustainable solution.

When rambunctious boys mess about with teacher Y, the Principal might say, "have you tried building relationships/giving choice/being more engaging like teacher X is?". Cue teacher Y observing teacher X, seeing their great relationship and well-behaved kids, but having no idea of how to achieve it. Teacher Y doesn't see the hard work that went into reinforcing boundaries at the beginning of the year, just the results of that - good relationships and behaviour. This can lead to attempts to replicate the part that is seen but not the hard work in the background that led up to this situation; putting the cart of good relationships before the horse of reinforced boundaries.

Boredom is normal; frustration is normal; anxiety is normal - can we stop trying to eliminate all negative emotions? Of course, when such emotions become paralyzing, help should be sought and will be. Nevertheless, let's be very clear about how the process of referrals works in many schools. The first diagnosis is often teacher complaints about students. This diagnosis comes from the desire to "solve" that behaviour and a useful way to solve it is by finding something that is "wrong" with the child in question. This often happens when a lack of consistency has created a situation where rambunctious boys are confused about expectations.

The rush to refer to an external expert is particularly ironic given that psychological sciences have quite a unique way of quantifying mental disorders. Anyone want to have a go at clearly defining one unit of narcissism vs one unit of autism in an uncontentious way? If you can do that, you will win a Nobel prize in psychological sciences. This measurement problem is overcome by talking about a spectrum. ADHD isn't a specific neurobiological state but rather a range of behaviours which can become problematic associated with a particular neurobiological state. If the behaviour is no problem, then there is unlikely to be a diagnosis. Who decides when and if the actions are problematic? Well, here we reach a certain circularity. The school will observe disruptive behaviours, and because "all behaviour is communication," they start looking for the underlying cause. They start a "search" in perfect faith, for what might be "wrong" with a child. The parents and the professionals take such a referral to mean there is a problem.

Perhaps most ironic of all in this circularity is that the Connors test then comes back to school for teachers to fill out! A Connors is a battery of questions designed to evaluate a range of psychological disorders and compare them to "normal" behaviour that parents, and sometimes teachers, are asked to fill in. The teachers who raised the flag in the first place are unlikely to change their mind given the subjectivity and ambiguity of the questions contained in the Connors. The teacher is thinking, I gave a choice, I tried to build relationships, I made my classes super-engaging, and this kid still messes about ERGO there must be something wrong. Of course, they'll compare Johnny with Sarah or even Alan, who don't behave like that; Sarah and Alan are the normal ones because they behave "well!"

The worst part of all this is that it means those children who do have to deal with quite severe and significant health issues aren't given the support they need. What's normal is that a school should have a set of rules that discourage students from making the wrong choices. The nudge theory of economics says that changing behaviour is a case of making it more difficult to the wrong thing in the moment of choice. Humans respond to in-the-moment cues much better than long lectures in the hall way at break. I would summarise the creation of healthy school culture in that way, making it hard to do the wrong thing, thus allowing compassion, kindness, and learning to flourish. If it's easy to disrupt, to tease, to insult, it will happen - despite lots of "serious chats". How do you make it hard to do the wrong thing? As a base-line, you have clearly expressed rules and consequences. There is a "way we do things around here" that is considered a high priority for leaders and teachers. It is normal for a kid to want to mess about just as it is normal for adults not to want them to mess about and to take actions to reduce the opportunities to mess around.

By saying, as a default, all behaviour is the communication of an unmet need, we implicitly reduce children's autonomy. This mentality assumes children aren't able to see why they do things. The "need" is undefined and could range from severe trauma to not having slept enough last night. By seeing the behaviour in terms of the "underlying problem", we fail to allow children regular healthy opportunities to make mistakes, be defiant, and challenge authority. Worse than the overdiagnosis itself is that we miss opportunities to focus on those cases when a diagnosis is really needed but the behaviour is less overtly challenging. We can become obsessed with thinking in terms of, there must be "something else going on" with the badly behaved kids and thus miss when there really is "something else going on" with any of the children we work with. When you have high expectations and use a warm-strict system, you also have compassion, support, follow-up, and yes, when necessary external services! The difference is, this is not always directed to boys who challenge authority.

Of course, all behaviour is the communication of an unmet need is accurate in quite an obvious way. Actions and words are intentional and contain information about what you want and need. The problem is when we attribute WHAT children are communicating to trauma or an underlying disorder, in other words, we don't take it on face value. Then comes the need to get to the "bottom" of the behaviour - in practice; this means referrals and the whole psycho-disorder-industrial-complex. The children most likely to suffer from this are children from more challenging circumstances and of course, rambunctious boys.

There is a tension between the following statements: "They are just children" & "they are communicating an unmet need." I believe there are very few people who would disagree that the current epidemic of ADHD diagnoses is concerning. Parents and teachers should be aware of the underlying complex dynamics of the system. There are multiple feedback loops involved and quantifying any psychometric state is inherently problematic. It is usual for young men, in particular, to find it hard to finish things, to be distracted, and to be disorganized. It should be usual to hold them accountable and not see their inability to do it as representative of some underlying pathology. The current discourse around behaviour - behaviour is the communication of an unmet need - has led to an over-diagnosis of disorder or the "pathologization of childhood". Let's, as a profession, stop accepting meaningless banalities and work on creating a warm-strict, compassionate culture with high expectations for all our children, Kids Deserve It!

Comments

Post a Comment